2020 has been a rough year but it’s also been a year that’s been mostly marked with replays of some of my most beloved games. From crowd pleasers like Pokémon Platinum to more niche entries like Mistwalker’s The Last Story, I’ve replayed a lot in an eager attempt to fill in the gaps in my nonexistent backlog. In a year where most publishers released remasters and remakes, it only felt appropriate to look back on some of the series that defined my taste. And what better way to start than one of my personal favorites of all time, Cavia’s 2003 cult classic Drakengard.

My relationship with the Drakengard (or Drag-on Dragoon as it’s known in Asian territories) series is a long one and I’m no stranger to replaying these games in general. Yet this year’s replay felt different, somehow more engaging probably due to my knowledge of how far the series has gone since then. While its spin-off series, Nier has found much love in the west with the release of 2017’s Nier Automata opening up the rest of the series to the public eye, Drakengard’s success was mostly domestic while remaining in cult classic obscurity internationally. An unfortunate fate mostly due to the poor reviews its first entry received citing convoluted plot, awkward controls, and repetitive gameplay. Despite this, the series has endured in the hearts of those who loved it initially, myself included. If anything, its faults are its greatest strengths in creating its unique oppressive atmosphere. Intentional or not, Drakengard is a hellish experience that serves as a reminder that games don’t have to be a smooth experience for them to still be enjoyable.

Being the first entry in Yoko Taro’s long-running series as well as his directorial debut, Drakengard represents Taro’s design philosophy of “making weird games for weird people” exceptionally well. Drakengard, for better or worse, is full of ideas that went against the grain of standard videogame narratives at the time. From the opening sequence, Taro establishes the dark, gritty world of Midgard, a land ravaged by war largely due to a mysterious illness known as the Red Eye disease turning its victims into violent mindless husks of their former selves. From then on, we’re introduced to our main character, Caim, the crown prince of Caerleon, who is desperately fighting off the neighboring Empire, manipulated by the same cult who controls the spread of the Red Eye disease bent on the destruction of the Seals, objects magically linked to a woman known as the Goddess of the Seal who just happens to be Caim’s sister, Furiae. It’s a lot to take in but suffice it to say, all is not well in the world of Midgard and it’s up to Caim and his draconic companion, Angelus to protect what they value most. While Drakgengard’s setting might not be the most unique compared to other dark fantasy series, its character drama is what separates itself from the other works in its genre.

To put it simply, Yoko Taro isn’t afraid to make his characters messy. While most other contemporaries at the time were content with establishing their main conflicts as black and white, Drakengard revels in the grey. Largely stemming from Taro’s idea that: “you don’t have to be insane to kill someone — you just have to think you’re right”, this “immorality” takes center stage in the development of many of Drakengard’s characters. For example, Caim, our main protagonist, while bitter due to the brutality he’s had to endure, fights on in honor of protecting his sister and as a way to seek retribution for the loss of his parents. It isn’t until later on in the story you witness Caim slowly become desensitized with killing and it becomes clear his intentions for fighting aren’t so clear cut. In reality, Caim isn’t fighting for the sake of anyone but himself. Fighting has only made Caim apathetic to those around him and through fighting, he attempts to sate the rage inside him.

Couple this with Caim’s sister Furiae, a sheltered princess harboring a deep incestuous love for her brother, and Inuart, a childhood friend of Caim’s, whose obsession with Furiae and inherent cowardice are deceitfully covered by a false veil of sincerity. Barring the many side characters, most notably, a grief-stricken mother turned cannibal and a forest recluse shackled by the guilt of his pedophilic tendencies, Drakengard has a multitude of heavy themes that are represented within its deeply flawed but captivating characters due to the versatility they add to the narratives the game explores.

Perhaps one of the most compelling story aspects is the fact that the story never seeks to redeem these characters in any way or form. We understand their motivations for acting the way they do and how their past has shaped them but the story never forgives them for being complicit in their own personal transgressions. Much like real life, the aftereffects of trauma are not so easy to erase. Due to this, many of Taro’s characters seemingly inhibit self-destructive tendencies, a sort of inescapable nihilism that’s become somewhat of a series staple ever since. All of this suffering is not for naught, however. as though each character’s pain, we begin to learn more about them and as a result, it humanizes them. The character’s Taro creates often represent the cruelty of reality or in his own words, “That is why people can empathize with the suffering of characters … The reason my games are chaotic is that the world is chaotic.”

But enough of that philosophical nonsense, let’s talk about where you take part in this nightmare yourself. Let’s talk gameplay.

I’ll be completely honest, when it comes to actually playing Drakengard it’s not something I can describe as objectively fun. Awkward yet manageable controls, a claustrophobic, over the shoulder battle camera (which Taro himself laments), and awkward enemy movement lead for a stiff Musou-styled game that’s serviceable but leaves a lot to be desired. For the majority of the game, you’ll be engaging in ground combat fighting seemingly endless waves of soldiers with some standard forms of attacks. Sure there are a multitude of weapons to discover and choose from but most of the time you’ll find one or two weapons and an optimal combo you’ll be repeating mixed in between your standard directional dodging. While all of this might seem highly unfavorable and slightly monotonous, I still had a decent bit of fun with the ground combat. The maps are often large and sprawling and fighting wave after wave creates a sort of natural rhythm to each level (or “verse” as the game calls it) diversified with objectives that are typical to other warriors style games of its era.

Paired with the wonderfully scored and also heavily experimental soundtrack by the talented Nobuyoshi Sano of Ridge Racer and Tekken 3 fame. Utilizing a multitude of samples from various classical pieces such as Dvorák’s Symphony No.9 the soundtrack puts their own spin on these beloved sounds and creates a harsh droning soundtrack creating an oppressive ambiance in parallel to the gameplay working in favor of enhancing the game’s ongoing narrative on the horrors of war and the insanity of those who actively participate in it. In a game where you are often cutting down thousands upon thousands of soldiers hellbent on killing you it only makes sense for the soundtrack itself to be oppressive as the cacophony of strings and loud blaring horns create a sense of tension in the actions you take and the gravity of the situations Caim faces.

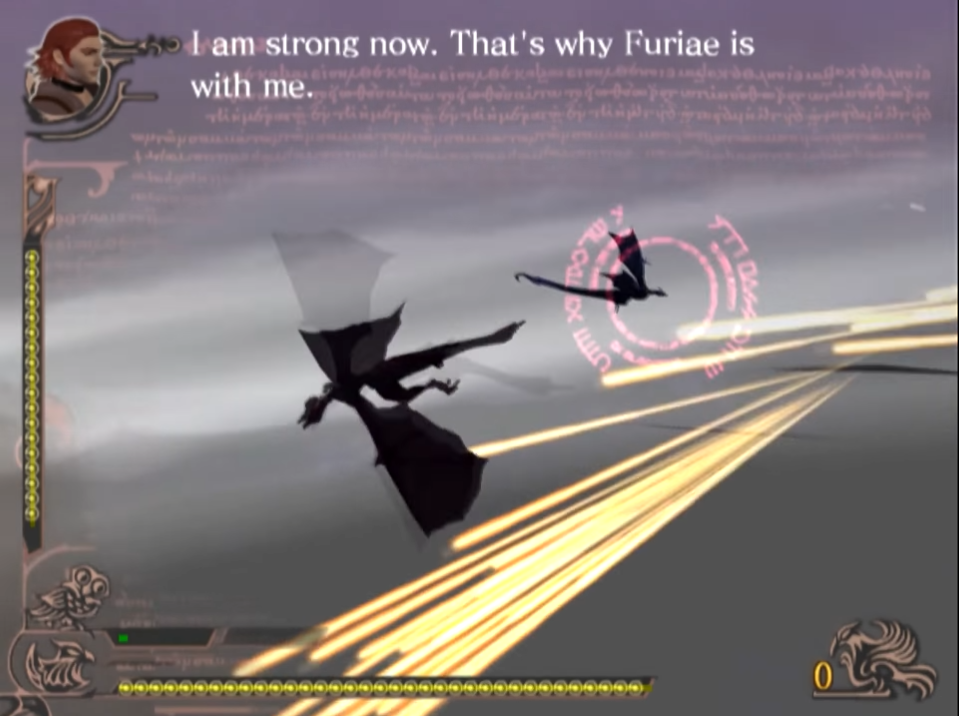

While the ground combat might leave much to be desired, it isn’t a Yoko Taro game if there aren’t multiple modes of gameplay involved and the other half of Drakengard’s main playtime is largely aerial combat. Here you’ll mostly be piloting Angelus, Caim’s dragon with whom he has formed a pact, and shoot down enemy structures and aircraft. These segments while making use of a different control scheme actually help to spice up the monotony in between ground missions while also just being quite fun to play in general. Aerial combat for the most part plays similar to the Ace Combat Series, an element most likely attributed to the fact that lead programmer Toshiyuki Koike had previously worked on Ace Combat 3: Electrosphere. Comparatively, the aerial segments control quite nicely and the verses themself don’t drag on (see what I did there?) as long as a lot of the ground segments do.

While it’s highly unlikely the developers intended for Drakengard’s gameplay to be so stiff and unintentionally punishing at times, the gameplay often works in its own favor towards the story as perhaps controls unintentionally can make some moments simulate the same desperation felt by the characters within the game’s narrative and help to amplify the tension and significance of some of the game’s events that unfold. This is only further emphasized towards the game’s end in which Caim’s fight with Inuart is marked by a significant difficulty curve as it is one of the lengthiest aerial segments in the game. While being notable in being a tough but fun segment, this is also an important moment within Drakengard’s narrative as Inuart’s betrayal further spurs Caim’s anger, and both are equally prepared to take the life of their very own best friend. A moment only highlighted by its rapid pace marked by tight windows of attack and blindingly rapid evasion of projectiles on both sides often resulting in the camera struggling to catch up. This isn’t a friendly sparring match, these are two emotionally wounded humans fighting to the bitter end as a result of all their pent up frustration manifested within themselves as each other. Yet, despite all these faults and frustration I had with this segment my first time through, it remains extremely memorable in retrospect and one of the very few that is reinforced by its gameplay.

Similarly, towards the end of one branch in Drakengard’s multiple endings, Caim faces a group of child soldiers which he brutally and relentlessly slaughters despite their cries which the game very much emphasizes. Yet despite all the protests given by Leonard (your party member who’s character arc remains pivotal to this moment), Caim continues until all of them lie dead. While this section’s significance is marked by its symbolic representation of Caim’s unending anger and further descent into madness, it also represented a slight moment of hesitation for me initially. Caim is no stranger to slaughter and neither is the player for actively participating in moving Caim along this despair stricken path of death and destruction, yet despite all that, the cries of the children as you cut them down only left me with a sense of guilt despite the fact what I had been participating in earlier had been no different. Despite all this, I don’t think Taro’s intention here is to merely punish the player and act holier-than-thou but to reinforce the tragedy of Caim’s actions and the repercussions that war entails.

While Drakengard might not be the strongest in the gameplay department its story and characters are definitely worth exploring. After all, it’s laid the groundwork for the games that came after as the series has slowly picked up internationally and Drakengard has managed to crawl out of obscurity to become a sleeper hit for those looking for a different JRPG experience. It’s a game I look forward to whenever I replay it and one I’ll continue to enjoy in future replays. Playing it might feel like hell but to me, Drakengard’s greatest strengths are in its objective weaknesses.

Time and time again, I find myself drawn to the grim narratives of Drakengard’s characters tinged with a sense of nihilism that serves as a poignant reminder of humanity’s weaknesses in the face of despair. Perhaps, the reason Drakengard resonated with me so much more this year than it had previously was because of the escapism its story provided for me. In a time in which public sentiment is mostly marked with a sense of dejection, you’d think playing a game that’s narrative largely revolves around despair and madness would only do the opposite yet, despite that, Drakengard with all its reveling in despair only served to remind me that reality is not as cruel as it seems and the human struggle is always constant. Flawed or not, Drakengard is simultaneously a compelling and nightmarish narrative on moral ambiguity in its exploration of humanity through violence. It’s a nightmare I’d dare not wake up from.

Recent Comments